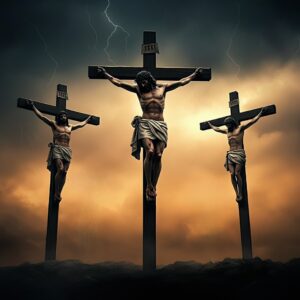

The crucifixion of Jesus Christ is one of the most significant events in Christian theology, representing sacrifice, redemption, and the fulfillment of prophecy. The Gospels provide detailed accounts of Jesus’ crucifixion, describing His suffering, the method of His execution, and the significance it held for His followers. Yet, as scholars and archaeologists have sought to understand the historical and cultural context of crucifixion, a wealth of information about this brutal Roman practice has emerged. While much remains unknown, archaeological evidence combined with historical sources provides insights into the methods and purposes of crucifixion and how it relates to the Gospel accounts.

The crucifixion of Jesus Christ is one of the most significant events in Christian theology, representing sacrifice, redemption, and the fulfillment of prophecy. The Gospels provide detailed accounts of Jesus’ crucifixion, describing His suffering, the method of His execution, and the significance it held for His followers. Yet, as scholars and archaeologists have sought to understand the historical and cultural context of crucifixion, a wealth of information about this brutal Roman practice has emerged. While much remains unknown, archaeological evidence combined with historical sources provides insights into the methods and purposes of crucifixion and how it relates to the Gospel accounts.

This article explores Roman crucifixion practices, examining archaeological findings that shed light on Jesus’ execution and the cultural implications of crucifixion in the Roman world.

The Origins and Purpose of Crucifixion

Crucifixion was a form of execution used by the Romans and earlier civilizations to punish, deter, and publicly humiliate those deemed threats to society or the state. Although its exact origins are unclear, crucifixion was used by the Persians, Carthaginians, and Greeks before the Romans adopted and refined it as a means of state-sanctioned terror. By the first century A.D., crucifixion had become the preferred method of execution for non-citizens accused of heinous crimes, particularly insurrection, rebellion, and treason.

For the Romans, crucifixion was not merely about punishment; it was a public spectacle designed to reinforce their authority and power. Victims of crucifixion often suffered prolonged agony, exposed to the elements and humiliation as they slowly died. The act served as a grim reminder of Rome’s power and the consequences of defying its rule. Thus, crucifixion was both a political tool and a psychological weapon, intended to demoralize and deter potential dissenters.

Roman Crucifixion Practices

Roman crucifixion was a multifaceted process involving scourging, preparation, and nailing or binding of the condemned to the cross. While there was some variation in how it was carried out, the main elements typically followed a brutal but efficient process.

- Scourging

Before crucifixion, victims were often scourged or flogged as a preliminary punishment. The scourging was usually performed with a flagrum, a short whip embedded with pieces of bone or metal. This device would tear into the flesh, causing deep wounds and substantial blood loss, weakening the condemned before the crucifixion itself.

The Gospels describe Jesus’ scourging before His crucifixion, noting that Roman soldiers flogged Him, placed a crown of thorns on His head, and mocked Him (Matthew 27:26-31). The injuries inflicted by the scourging would have left Him severely weakened, hastening the suffering and physical toll of the crucifixion.

- Carrying the Cross

Following scourging, victims were often forced to carry the horizontal beam of the cross, known as the patibulum, to the execution site. In many cases, the condemned would carry only the patibulum, as the vertical post was often already stationed at the crucifixion site. This added further humiliation and physical exhaustion, as the condemned person, bleeding and weakened, was paraded through the streets.

The Gospels recount that Jesus was forced to carry His cross to Golgotha, the site of His crucifixion (John 19:17). When He could no longer bear the weight, Simon of Cyrene was compelled by the Roman soldiers to help carry it (Luke 23:26). This practice was consistent with Roman crucifixion protocols, underscoring the Gospels’ historical alignment with known Roman customs.

- Nailing or Binding to the Cross

Upon reaching the execution site, the condemned was either nailed or tied to the cross. Although not all victims were nailed, historical accounts and archaeological findings confirm that nailing was a common method, particularly for individuals viewed as significant threats. Nails were typically driven through the wrists (rather than the hands, as often depicted in art) to support the body’s weight, and the feet were either nailed individually or overlapped and nailed together to the vertical post.

The Gospels specify that Jesus was nailed to the cross (John 20:25), with Thomas later invited to see and touch the marks left by the nails. This detail is significant, as it aligns with archaeological evidence and historical accounts indicating that nailing was often reserved for individuals who were considered particularly dangerous or defiant.

Archaeological Evidence of Crucifixion

Archaeological evidence of crucifixion is scarce, primarily because the Romans viewed crucified individuals as criminals and denied them honorable burials. Bodies were typically left on the cross to decay or were discarded in mass graves, making it rare to find preserved remains of crucified victims. However, several significant discoveries provide insight into crucifixion practices, including a key find in Jerusalem that has deepened our understanding of Jesus’ execution.

- The Discovery of Yehohanan’s Remains

In 1968, the remains of a crucified man named Yehohanan were discovered in a burial site in Givat HaMivtar, near Jerusalem. This find is one of the few archaeological pieces of evidence for crucifixion from the Roman period. Yehohanan’s right heel bone (calcaneus) still contained a nail that had pierced through it, anchoring it to a small piece of wood. This find provided unprecedented physical evidence of crucifixion and confirmed several aspects of the Gospel accounts of Jesus’ death.

The position of the nail through the heel bone suggests that Yehohanan’s legs were either nailed individually on each side of the cross or together with one foot over the other. The nail was bent at the end, likely hitting a hard knot in the wood, which prevented its removal after Yehohanan’s death and allowed it to be preserved with his remains. This discovery confirmed that nails were indeed used to affix the feet to the cross, matching descriptions of Jesus’ crucifixion.

Additionally, the presence of Yehohanan’s burial in a Jewish tomb challenges the assumption that crucified individuals were universally denied proper burials. This aligns with the Gospel account that Joseph of Arimathea, a wealthy Jewish council member, sought permission from Pontius Pilate to bury Jesus, which was granted (Matthew 27:57-60). Yehohanan’s remains serve as rare and valuable evidence supporting the New Testament’s descriptions of Roman crucifixion practices.

- Nail Marks and Remnants of Wood

The discovery of nails used in crucifixion is another form of evidence that supports the Gospel accounts. Roman nails were typically about five to seven inches in length, with a square shaft, making them ideal for piercing bones and holding the body in place. Although finding actual crucifixion nails associated with ancient skeletons is rare, some nails from this period show signs of wear that suggest they may have been used in crucifixions or other forms of binding.

Archaeologists have found remains of wood associated with some nails, often identifying remnants of olive wood, which was common in the region. These findings align with the descriptions of the cross being constructed from available local materials, supporting the theory that crosses were built on-site, adding to the humiliation of the condemned. This approach aligns with the swift and ruthless efficiency of Roman crucifixion practices.

- Ancient Graffiti Depictions of Crucifixion

One of the most striking examples of ancient crucifixion imagery is the Alexamenos Graffito, discovered on a plaster wall in Rome and dated to around the second century A.D. This graffito depicts a man worshipping a crucified figure with the head of a donkey, with the inscription “Alexamenos worships his god.” This crude caricature reflects the disdain that Romans held for crucified individuals and the contempt with which they viewed the Christian faith. For early Christians, the cross was not only a symbol of Christ’s suffering but also an object of ridicule in the Roman world.

The Alexamenos Graffito provides indirect evidence of the significance of crucifixion in Roman society, especially concerning early Christianity. It reflects the stigma attached to crucifixion, highlighting how Christians embraced this symbol despite its association with shame and punishment.

- Literary and Historical Accounts of Crucifixion

While archaeological evidence of crucifixion is limited, historical sources provide detailed accounts that confirm and supplement what archaeologists have uncovered. Roman writers, including Tacitus, Josephus, and Seneca the Younger, describe the brutal nature of crucifixion and its widespread use as a form of punishment for criminals and dissenters.

The Jewish historian Josephus, writing in the first century A.D., records the use of crucifixion in the Roman siege of Jerusalem in 70 A.D. He describes how Roman soldiers crucified Jews outside the city walls, sometimes experimenting with different positions to increase suffering. Tacitus and Seneca also describe crucifixion as a punishment used specifically for its cruelty and ability to inspire fear. These accounts align with the New Testament, where the cross serves as a symbol of both suffering and salvation.

Crucifixion and the Gospel Accounts

The archaeological and historical evidence of crucifixion provides a framework for understanding Jesus’ crucifixion as described in the Gospels. The alignment between Roman practices and the Gospel accounts strengthens the case for the historical accuracy of the crucifixion narrative and offers insights into the meaning of Jesus’ death within this context.

- The Physical Realities of the Cross

Understanding the physical suffering involved in Roman crucifixion provides insight into the depth of Jesus’ sacrifice, as described in the New Testament. The scourging, forced carrying of the crossbeam, and nailing of the hands and feet would have caused excruciating pain, aligning with the Gospel accounts of Jesus’ suffering on the cross.

The physiological effects of crucifixion—intense pain, difficulty breathing, dehydration, and eventual asphyxiation—underscore the brutal reality of this punishment. For early Christians, Jesus’ willingness to endure such suffering was seen as an act of profound love and redemption, giving theological weight to the cross as a symbol of salvation.

- The Cultural Stigma of Crucifixion

The Romans viewed crucifixion as a punishment reserved for the lowest members of society, and it was meant to strip the condemned of any dignity. For early Christians, the notion that their Savior was crucified was initially a source of scandal, as reflected in Paul’s writings, where he describes the “foolishness” of the cross to nonbelievers (1 Corinthians 1:18). Yet the fact that Jesus, the Messiah, willingly endured this form of punishment became a central aspect of Christian theology.

The discovery of the Alexamenos Graffito underscores the scorn associated with crucifixion, yet it also shows how early Christians subverted this symbol of shame, transforming it into a symbol of faith and redemption.

Conclusion: Archaeology and the Cross

While archaeology cannot “prove” the resurrection, it provides crucial insights into the historical reality of Roman crucifixion practices. Discoveries like the remains of Yehohanan, crucifixion nails, and Roman graffiti give us a glimpse into the brutality of crucifixion, corroborating the Gospel accounts of Jesus’ execution.

These findings illuminate the suffering Jesus endured and the cultural implications of His death, revealing the cross as a potent symbol of both the cruelty of Roman justice and the transformative power of faith. Through archaeological evidence and historical accounts, we can better appreciate the significance of the crucifixion, not just as a moment in history but as a pivotal event that continues to shape the lives and beliefs of millions worldwide.